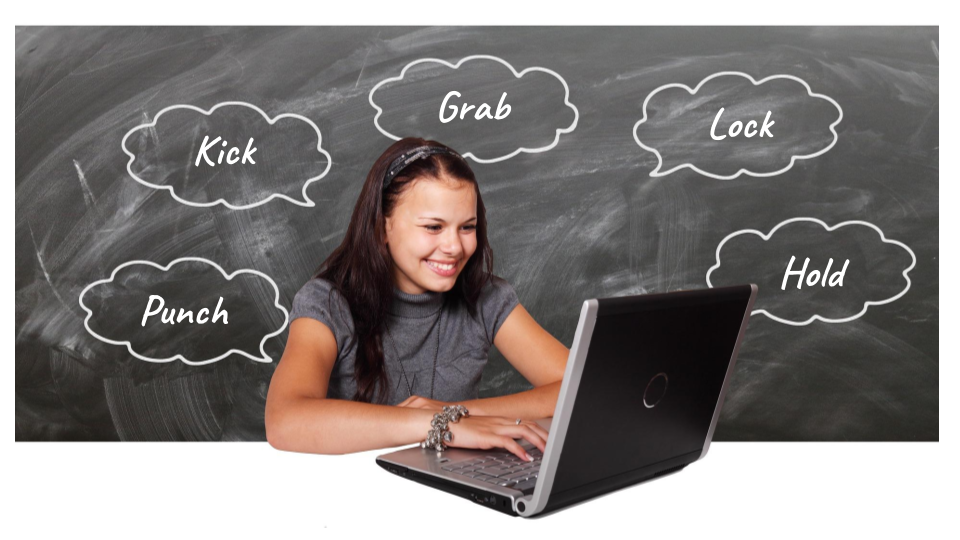

Based on Grandmaster Ed Parker’s Web of Knowledge, our curriculum organizes our techniques into nine categories or groups. These make up the core curriculum and are the foundation of the numbered techniques, for example, Punch Defense 3, Kick Defense 1, Grab Defense 4, or Hold Defense 8.

- Punch/punches: The attacker strikes the victim with a hand, elbow, or arm

- Kick/kicks: The attacker hits the victim with a foot, knee, or leg

- Grab: The attacker seizes the victim with no immediate follow-up action by the attacker

- Tackle/takedown: The attacker throws, flips, or knocks the victim to the ground

- Push: The attacker shoves or forces the victim backward

- Hold/hug: The attacker seizes with restriction of the victim’s body movement and limits to the victim’s responses

- Choke/lock: A more severe restriction of the victim’s body movement with the likelihood of broken limb, consciousness, or death

- Weapon: The attacker strikes with a club, stick, knife, or gun

- Multiple attackers: Multiple opponents attack the victim

These groups represent the technique curriculum in a distributed, balanced manner. Think of it as a matrix for learning and internalizing the material.

Why is the curriculum organized in this fashion? When I began training, we were taught material during classes. Many of them didn’t have official names, and different instructors taught different techniques. As a student, this wasn’t very clear. At testing, I had lots of information, but the testing stress caused me to forget some of the moves I knew.

My students also had difficulties with a random assortment of grab escapes, animal Kempos, and other tricks. During my children’s class, I began assigning names to fundamental techniques so the kids could have a mnemonic to remember the move. I would also add verbal queues to assist memorization.

During our adults’ and children’s rank tests, the adults complained. The children could remember the material better. The adults wanted to have names or identifiers for all the techniques. That was a reasonable request.

To develop this practice, I researched how other teachers organized their curriculum. Grandmaster Ed Parker had a fantastic idea in his five-volume opus “Infinite Insights of Kenpo.” I adapted his web of knowledge to my problem.

It’s not an exact copy because I have a different set of techniques than the American Kenpo Karate system. Also, we use other identifiers instead of fancy names. But this use of numbers as naming identifiers has an added benefit; there is no cap to the number of family techniques.

When I started teaching, I was a third-degree Black Belt. I didn’t know all the material for the system. By fourth-degree, I had learned additional techniques that fit well into the curriculum. If I had numbered all my moves as I knew them, there wouldn’t be any rhyme or reason for the order. Using the family group method, I can keep all the chokes together, not mixed willy-nilly with pushes and grabs.

Another benefit is now you have identifiable techniques for chokes, pushes, grabs, holds, and locks. It’s easier to recall a lock defense named Lock Defense 5 rather than Escape 24. A teacher should set all the students up for success.

Look at the family groupings as a way to understand the big picture of your martial arts material. The curriculum helps you learn the material, remember the techniques, and provide a predictable framework for how things work together. I hope that this concept proves fruitful for my students. After 30 years of teaching, I am always looking for ways to improve my teaching and martial arts skills.

If you ever wondered why the techniques have odd names, now you know. I hope this answers any questions you may have. Your San Diego and Chula Vista instructors will help you if you have any lingering concerns or questions. Remember, we’re here to help you become an outstanding version of yourself, using Karate as a tool.